|

Story By Mike Comerford.

MALABON, PHILIPPINES - A 13-year-old boy crawls out of a curtained, wooden box attached to the wall of a crowded prison cell. Inside the box, an older man reclines, staring out. MALABON, PHILIPPINES - A 13-year-old boy crawls out of a curtained, wooden box attached to the wall of a crowded prison cell. Inside the box, an older man reclines, staring out.

In these concrete cells, only the bed-sized boxes along the walls afford privacy. Other inmates sit, shoulder to shoulder, nearby on the floor.

Sometimes, the boxes are used for sex. And when minors and adult criminals occupy the same cells, the opportunities are rampant.

"God knows what was going on in that box just now," the Rev. Shay Cullen says as he walks the hallways of Malabon Jail on the outskirts of Manila.

Twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, the Irish-born Cullen is on a mission to save youngsters jailed with adults from both abuse and the flood-prone, oppressive cells.

The Philippine Jesuit Prison Service, a Catholic mission, estimates as many as 20,000 minors can be incarcerated on the islands. Most are street children, Cullen says, an increasingly common occurrence around the world.

The numbers of boys and girls who are street kids in the Philippines have been estimated by some advocacy groups at more than 1.2 million - many of whom are working as pickpockets, drug dealers and prostitutes.

Those jailed face horrific conditions fueled by a lack of social workers and funds. A U.S. State Department report says these metro Manila jails are operating at 323 percent capacity. The amount spent on food per inmate is 63 cents each day.

On this hot day, Cullen visits two prisons with about 80 minors in metro Manila - Malabon and Navotas - before heading back to the children's home he built north of the former U.S. naval base at Subic Bay.

Accompanying Cullen, Daily Herald journalists are the first U.S. media to see the boys suffering the indignities and hardships of an incarceration grown men can barely endure.

Some critics blame inadequate government programs. Others blame inaction by the church in a country that is 83percent Catholic.

The government has programs designed to get youths off the streets, but a population expected to double in 29 years means the problem will only continue to grow.

An adult world

"A lot of these boys are innocent, but they shouldn't keep them here (with adults) even if they are guilty," Cullen says, as two assistants trail him, taking names of minors to track.

Cullen is a founder of PREDA Foundation Inc., or People's Recovery, Empowerment and Development Assistance Foundation. It's a Philippines-based group trumpeting causes often linked to the "liberation theology" movement focusing on advocacy for the poor.

At the Malabon jail, a separate wing for minors is being built, but Cullen and others want children either at his PREDA home or juvenile homes while they await trial.

Meantime, PREDA purchased ceiling fans "to keep the kids from heat exhaustion and the smell," Cullen says.

Malabon and Navotas are notoriously flood-prone municipalities. Rancid flood waters sometimes fill the cells, forcing inmates, young and old, to perch on whatever is available or stand in sewage for hours - sometimes all night - until the flood waters recede.

The overall conditions at Malabon jail are said to be better than at other jails, but Cullen is suspicious.

Juvenile cells are being built adjacent to the women's wing. Overcrowding and signs of abuse are just as apparent there.

In the hallway outside the main women's cellblock, a male guard is seated, leaning back against the wall, leisurely getting a manicure from a female inmate seated to his left. His right hand rests easily on the inner thigh of another woman to his right.

In the common yard, relatives gather to visit in the stifling heat. They sit in the shade of a tarp hung over a basketball court. Only the muffled sounds of traffic outside the jail walls can be heard, reinforcing the sense of isolation.

Cullen later says he is told the warden demands bribes from relatives wishing to see their children.

Today, a young woman walks from under the tarp to a lone karaoke machine facing the jail cells. She picks up a microphone, smiles, and begins singing in the sun-drenched yard.

Hundreds of inmates peer out from their cells as she sways and sings a syrupy sweet Philippine pop song about love and longing.

Her song sounds like an effort at solace in a place, as Cullen says, where only God knows what is happening.

A place like no other

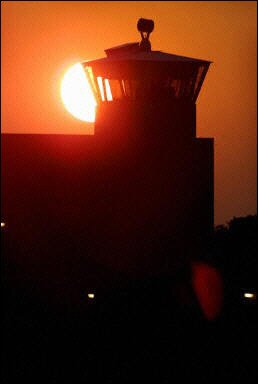

Evening approaches and the sun is about to set on Subic Bay as Cullen's van climbs the winding road up the hill to the PREDA home.

With a three-story, Spanish-style exterior designed and built by Cullen, the PREDA home is part administrative headquarters and part dorm complex, with buildings to house, educate and feed about 60 boys and girls.

In a classroom , 24 boys sit on plastic chairs. Written on the chalkboard is "What do I want to be?"

Hands fly up and answers follow - a pilot, a lawyer, a teacher, an army man, a nurse.

No one says ex-con or criminal, but that most likely was their fate had Cullen not plucked them from local jails.

Some admit they were being abused in their cells by adults. Others are too ashamed to admit anything.

With thick, bushy black hair, Alberto, 12, faces two counts of rape. Cullen says Alberto may be guilty, but he also may just have been a nuisance to someone who trumped up charges.

Alberto isn't here because of innocence or guilt, Cullen says. He's here because 12-year-olds shouldn't be in jail with adult criminals and perverts.

"I know it is hard to believe, but I used to smile all the time," Alberto says unsolicited, as if he hoped PREDA would help restore his carefree nature.

A life's work

Cullen began housing drug dependents here in the 1970s, then moved on to housing under-aged girls, who were involved in the sex industry. A few years ago, he added care for imprisoned youth.

Psychotherapists, teachers and social workers on site do the daily work when Cullen is out raising funds or awareness.

Since he arrived in 1969, the St. Columban priest has championed a wide range of causes from indigenous tribes' rights to a winning campaign to close the naval base on Subic Bay.

The 61-year-old priest regularly organizes "rescues," accompanying authorities into strip clubs to take underage "bar girls" away from that life.

He's personally arranged for pedophiles, some American, to be arrested. He has rescued hundreds of minors in more than three decades of work.

He believes death squads operating on the southern island of Mindanao are targeting street kids to do their bidding. It's an allegation Davao City officials deny.

His efforts have earned him enemies among sex industry business owners, local politicians and even among some from the U.S. Navy after he sued it for corrupting Subic Bay-area morals.

Critics say his rhetoric is too strident. He says he can't see how people rest knowing what he knows.

"Jesus is found among the poor and oppressed," Cullen says. "I can't understand how anyone can't be outraged."

Cullen knows a 60-child home and a few ceiling fans in city jails don't seem like much in the face of such staggering cruelties. There are times, he says, when he feels outrage, frustration, helplessness. But he's not about to quit.

"I'm very optimistic," he says. "I wouldn't be able to survive here if I wasn't an optimist."

Pessimistic waters

The water flows slowly under a nameless bridge between Malabon and Navotas.

It carries bright blue plastic bags, orange juice boxes and other trash with slogans about bursts of flavor and good times.

The water is so dark, the colorful waste looks like confetti floating in a black night.

Beneath the bridge, a child no more than 10, rows a makeshift polystyrene raft the size of a surf board. He uses small pieces of wood for oars. His thin, marionette-like arms row as he searches the water for recyclables - plastics, cardboard, foil bags.

Above, a group of boys about his age sees he's being watched by Cullen, who has pulled his van to the side of the road to take photographs he may use to depict the depths of poverty.

The shirtless, barefoot boys run across the bridge toward him, laughing mischievously.

Many Philippine children like to look happy for cameras, making their deplorable circumstances difficult to capture.

Bright-eyed and slightly out of sync, the three showoffs jump off the bridge with gleeful abandon into what amounts to an open-air sewer.

Their faces emerge, smiling, of course, as discharge from Manila floats by.

And a lanky, gray-haired Irish priest stands on the bridge above, agape at what he sees.

Moments later, he climbs into his van and drives away. The laughing boys still swim under the bridge behind him.

Cullen turns to focus on the road ahead, having once again seen the faces of so many children he cannot help.

|