Nelson Rand, Chronicle Foreign Service - Monday, June 14, 2004 Nelson Rand, Chronicle Foreign Service - Monday, June 14, 2004

Xaysomboune Special Zone, Laos -- At the age of 12, Moua Toua Ther was recruited by the CIA to fight communism. At 14, he lost his left hand from a bullet wound. At 17, the United States left him with three choices: surrender, flee or fight. He chose the last.

Thirty years later, his army long forgotten, Ther still holds out against the government of the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

"We thought the Americans would surely come back and help us," Ther says from his jungle hideout in the mountains of northern Laos. "But they never did."

Instead, he and a dwindling band of loyalists are battling for survival from continuous government military campaigns, with little assistance from their former paymasters.

"If they aren't killed by the military, they will die of starvation," said Ger Vang, a Laotian Hmong tribesman who now lives in California's Central Valley and works with a Hmong lobbying group pressing the Bush administration to do something.

In the 1960s and '70s, the CIA recruited mainly Hmong tribesmen from the hills of Laos to join a secret army to fight the communist Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese, who used Laos as part of a supply line known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail to move troops and equipment into South Vietnam. They paid a heavy price -- more than 17,000 were killed and an estimated 50,000 Hmong civilians died.

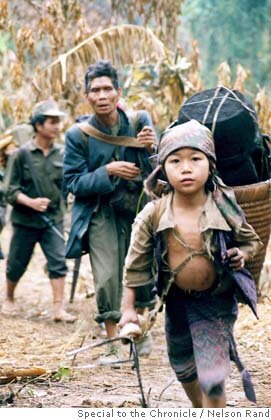

A Hmong family walks through the jungle as it flees government soldiers in northern Laos. A dwindling band of insurgents is waging a losing battle against a government military campaign, hunger and inadequate medical care. The future of thousands remains uncertain. Photo by Nelson Rand, special to the Chronicle

|

When U.S. forces withdrew from Vietnam in 1973 and the Pathet Lao assumed power two years later, thousands of Hmong fled to neighboring Thailand and eventually resettled in the United States, Canada, Australia and France. But some 15,000 Hmong guerrillas, along with pockets of ethnic Lao, Khamu and Mien, were unable to cross the Mekong River and fled into the hills.

On a recent trip to this tiny, land-locked Southeast Asian nation of 6 million inhabitants, a reporter traveled for three weeks with some 200 armed Hmong fighters and their families in the Xaysomboune mountains as they fled from a Lao army offensive in a war the government denies exists.

"There is no rebellion or group of insurgents," Lao foreign ministry spokesman Yong Chantalangsy has told Agence France-Presse.

Last year, two European journalists and their Lao American translator were sentenced to 15 years in prison for "obstructing police and possessing illegal explosives," for reporting on Hmong rebels, according to the Paris- based Reporters Without Borders. After an international outcry by Reporters Without Borders and other freedom of press groups, the three were released.

In recent months, Hmong activists say large numbers of Hmong fighters have been emerging from the jungles to surrender to government authorities, who have promised to resettle tribes from remote mountain areas to lowland villages and towns. But human rights groups say that since the government does not allow international observers to verify its resettlement efforts, they have no information about the fate of those who surrendered. There have been allegations of torture, imprisonment and summary executions.

"Until independent monitors are given access to people who have come down from the mountains, we just don't know what is going on," said Daniel Alberman, a researcher on Southeast Asia for Amnesty International.

Hmong commanders say there are 21 rebel groups in Laos with about 17,000 fighters and family members. Lao insurgent organizations with no ties to the Hmong veterans of the Vietnam War have sprouted in recent years, attacking government outposts and bombing markets and restaurants in the capital, Vientiane.

Ther's group of 2,000 has been surrounded by government troops since January and has lost 180 members, mainly noncombatants, say the group's commanders. Many of his rebels are ready to surrender if their safety can be guaranteed by a third party such as the United Nations. They say they are afraid of being imprisoned or sent to a re- education camp.

Ly Dang was interned in such a camp in 1975 after turning himself in along with thousands of officers, soldiers, police and government officials. He says he suffered harsh labor and torture until his release in 1983. Three years later, he joined Ther's group because of fear of being sent to another camp. "I just want to leave (the jungle), but it is very, very difficult," said Dang, now 50.

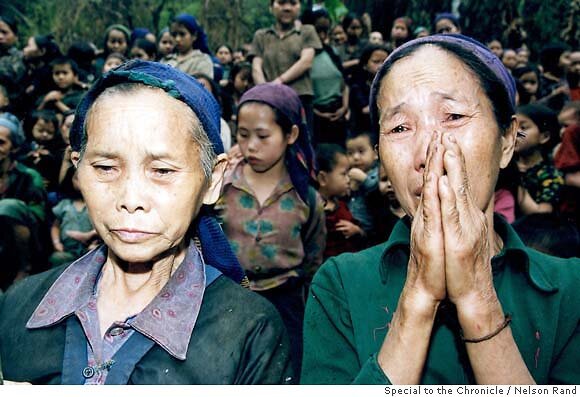

Hmong women in northern Laos desperately seek food and medical supplies for their beleaguered rebel families. Photo by Nelson Rand, special to the Chronicle

|

Ther's group has moved its makeshift jungle camps of bamboo shelters 12 times since the beginning of the year to avoid the Lao army. "We are the same as animals in the forest," said a 46-year-old fighter named Ly See Xeng, who claims to have participated in 122 battles in the past 30 years without injury.

The insurgents fight mainly with M-16 and AK-47 assault rifles and M-79 grenade launchers left over from the Vietnam War. Some ammunition had been bought with funds provided by Hmong Americans smuggled to the insurgents by corrupt army officials or sympathetic Hmong civilians.

But the Hmong fighters are in no position to launch an effective attack and typically fight either to defend themselves or simply harass government forces.

On a recent morning, a heavy mist filled a mountain valley, making it impossible for Hmong military leaders to see their target -- a government outpost. When the fog finally lifted, a commander radioed four men waiting for instructions to attack. They fired about 20 rounds and lobbed three grenades before fleeing.

The rebels lack food and medicine. Hunger has become their major enemy and there have been deaths from starvation. Since government offensives have prevented them from cultivating rice, their main food is a type of boiled yam.

Last month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution urging Lao authorities to stop alleged violence against Hmong rebels. The measure urges the Laotian government to provide human rights and humanitarian groups unrestricted access to closed military zones. It was only the second such measure specific to Laos passed by the House since the end of the Vietnam War.

At the urging of Sens. Herb Kohl and Russ Feingold, both Wisconsin Democrats, Secretary of State Colin Powell told a Senate hearing recently that he would contact U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan about sending a U.N. fact- finding mission to Laos to ensure the safety of Hmong rebels who stop fighting.

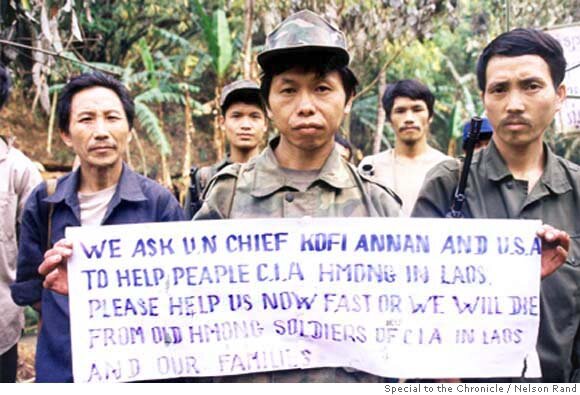

Ex-soldiers of a CIA-backed army that fought communist forces in Laos during the Vietnam War plead for international help. Photo by Nelson Rand, special to the Chronicle

|

"We must do all we can to help them and their families," Kohl said. "We will forever be indebted to these brave men and women and their families for the service they provided American forces during the Vietnam War."

Kohl and Feingold have also been pushing for additional funds to help the resettlement of 15,000 Hmong refugees in Thailand, most of whom are expected to join the 200,000 to 300,000 Hmong Americans, who have settled mainly in Wisconsin, Minnesota and California's Central Valley.

In the Central Valley, the Fact Finding Commission, a Hmong lobbying group based in Oroville (Butte County), has been pressuring Congress, the U.S. State Department and the United Nations to provide humanitarian aid to the Hmong in Laos and Thailand. They say preventing insurgents from farming is a new strategy for pressuring Hmong fighters to surrender.

"The Lao government is keeping the people far away from food sources," said Ger Vang, a commission member who fled Laos in 1979. Indeed, children in Ther's group are malnourished and wear torn clothes patched with bamboo thread. There is only one medic, who treats shrapnel wounds with traditional medicines from plants and trees and disease by invoking spirits. Some 16 people from Ther's group have died from illness since January.

"All we want is food, medicine and a place to live," said Xeng. "All I have is my family and my weapon."

"We helped America fight communism," added Ther. "In 1975, they left and we ran into the forest. Now we ask for their help. We are all about to die."

|